Asian Language Social Media Apps Are Influencing Asian American Voters' Election Choices

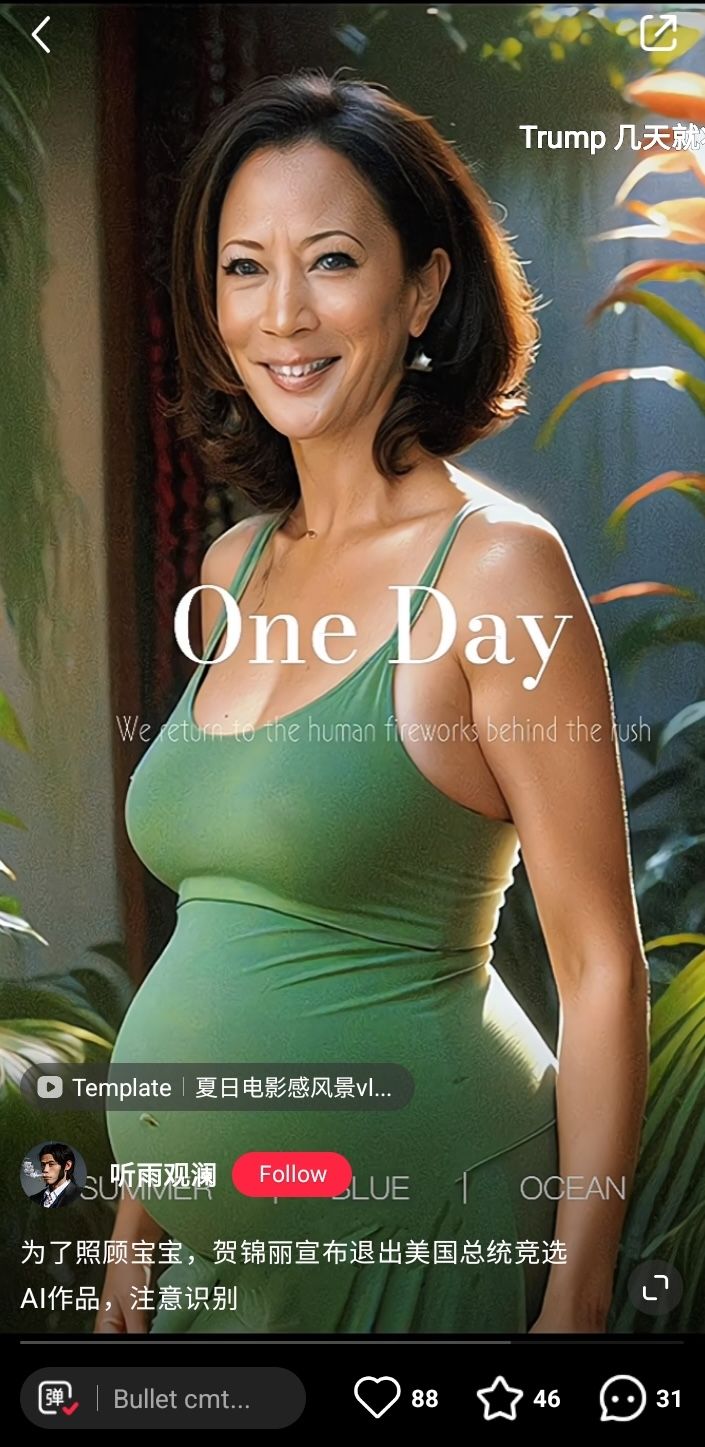

WASHINGTON – "Kamala Harris has announced that she’s stepping out of the presidential race to care for her baby," read a post on Little Red Book, a popular social media app among Chinese users. It was accompanied by an AI-generated image showing the 59-year-old Vice President pregnant.

"Then Trump will win the election in days!" one follower replied, while others seemed confused, asking for sources in the comments.

If you’re an Asian American who relies on social media in your native language for U.S. political news, this post might have appeared in your feed as well.

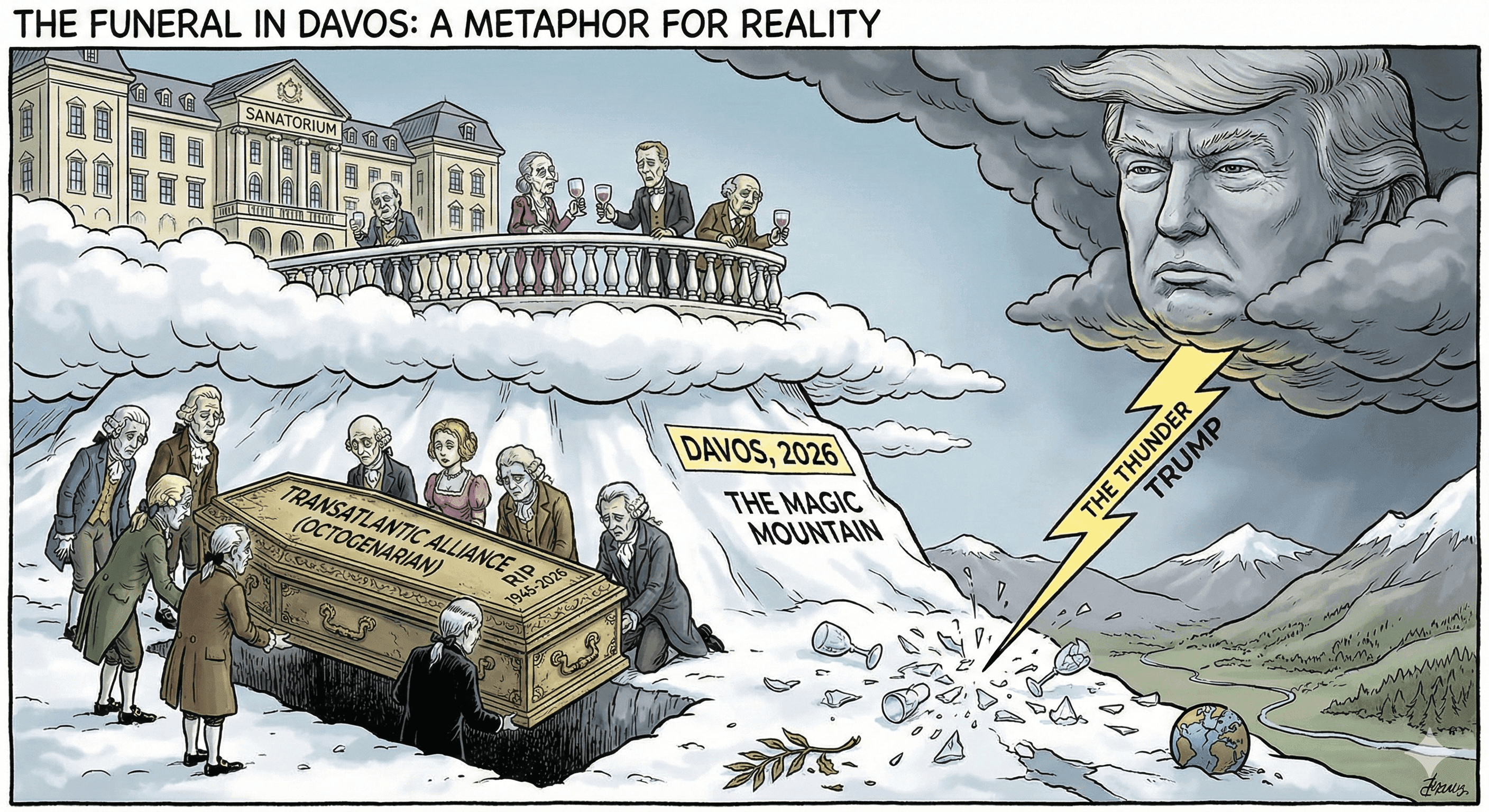

After each of the 2024 presidential debates, numerous articles were immediately posted on Chinese social media, ridiculing the American presidential candidates. WeChat, a prominent social media app popular among the Chinese-American community as well as Chinese citizens in the mainland, posted articles with headlines comparing the debate to a “variety show”, a “stand-up comedy” and describing the scene as “children bickering.”

These posts received millions of views, including from Chinese Americans who prefer getting their news through social media in their native language. Though misinformation and disinformation may be included, they are influencing this ethnic group’s voting decisions in November. Chinese Americans are not the only minority group that prefers receiving news in their native language. According to the 2024 Asian American Voter Survey, one in four Asian Americans gets news from non-English sources, with 6% relying on non-English language sources for most of their news, regardless of their specific ethnic group.

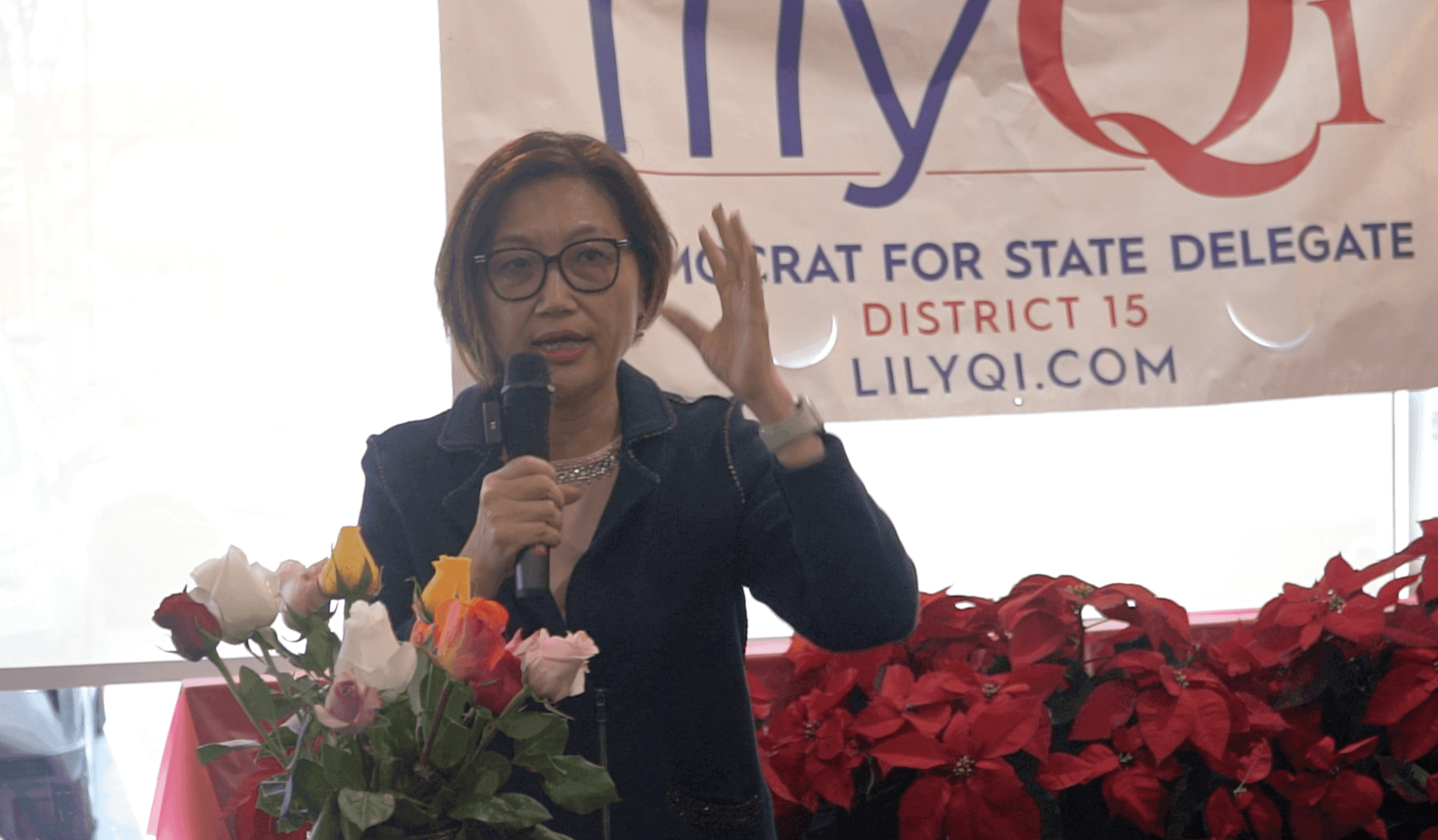

Lily Qi, the first Chinese-born state legislator in Maryland, noted that many of her friends in the Chinese American community, despite being highly accomplished professionals, still rely on Chinese-language social media for political information.

“It's good that we have such community media existing. But it's also risky because if that's your only source of information, it may not be accurate,” Qi said.

“I always feel that if U.S. news is translated into Chinese and people add in their personal opinions, I shouldn’t read it. After all, it has biases,” said Liu Ying, a 65-year-old Chinese American who recently received her American citizenship.

For example, Ying read an article in Chinese through WeChat saying the "extreme left" policies of President Joe Biden, Vice President Kamala Harris, and the Democratic Party are driving the U.S. towards communism. Additionally, some of these articles asserted that the Biden administration deliberately opened the southern border to enable undocumented immigrants to vote for Democrats. “Should I really believe this?” Ying said she had to ask herself with deep doubt.

Although in her mid-sixties, Ying is currently pursuing an English major at Howard County Community College. One of her motivations is to improve her ability to read English news and articles more fluently, allowing her to make informed decisions based on accurate information.

“I know that depending on your search history and cookies, [social media platforms] show you what you want to see. Like confirmation bias…they want you to keep using their app…editors are trained to get clicks,” said Kyung Mo Kim, 27, a George Washington University law student.

Kim was born in South Korea but later acquired his citizenship around the age of 12. Due to his early life living in South Korea, Kim spends some of his time reading news in Korean through social media platforms like KakaoTalk, which is widely used among Korean Americans, while keeping up with current American politics.

“Even if I am aware of these biases, it still affects me. It makes me more left-leaning or right-leaning on an issue depending on what I see,” Kim said.

For the past three years, Jenny Liu has been leading a project to better understand how misinformation and disinformation uniquely impact the Asian American community.

Liu and her colleagues at Asian Americans Advancing Justice – AAJC have been monitoring various social media platforms to identify who is spreading these information and what their motivations might be. Their goal is to understand why certain narratives resonate within the community.

After a “whack-a-mole” approach, they realized it’s a multifaceted issue and that “there's no silver bullet solution.” Despite this, they discovered that language barriers remain a significant factor, leading many Asian Americans to rely on social media in their native languages, where they feel a sense of intimacy.

According to a 2021 report by the Pew Research Center, only 34% of Asian Americans speak only English at home, while the remaining two-thirds use a language other than English with their families. Advocacy groups like Advancing Justice – AAJC therefore keep pushing for more language assistance for Asian Americans on critical issues such as voting and elections.

Meanwhile, Liu said that politicians from across the political spectrum should engage more directly with Asian American communities to make a personal impact. Otherwise, Asian Americans may have to rely on second-hand information from social media, which may include misinformation or disinformation without clear sources.

Currently, political outreach to the Asian American community is insufficient. According to the 2024 Asian American Voter Survey, only 42% of Asian American voters report having been contacted by either of the two major political parties this election season. This includes half who say they have not been contacted by the Democratic Party and 57% who indicate they have not been contacted by the Republican Party.

Asian American politicians play a vital role in connecting with the communities they represent. For instance, during this election cycle, Qi has organized several outreach campaigns among Asian Americans in collaboration with her Asian American legislative colleagues in Maryland. These events allowed congressional candidates to introduce themselves directly to local Asian American communities and address their concerns.

Qi shared the campaign information directly through social media platforms like WeChat. She was active in several WeChat groups where politically engaged Chinese Americans and community organizers gathered. She understands although WeChat sometimes contains misinformation and disinformation, it's where many in her community get their news.

WeChat proved to be instrumental in Qi's campaign when she ran for a seat in the Maryland state legislature. She connected with the large Asian American community in her district primarily through the platform, which helped her secure votes. So, whenever Qi wants to engage with this specific group after being elected, she continues to rely on it.

During a virtual seminar analyzing the 2024 Asian American Voting Survey, John Yang, President and Executive Director of Asian Americans Advancing Justice, emphasized the importance of recognizing the role that social media apps in Asian languages play.

Yang said that policymakers need to understand where Asian Americans are getting their news, so if they want to engage these communities, these social media platforms are the key. "These sources really do matter to our community and getting it right on these platforms really do matter."

Pingping Yin

Pingping Yin Hanna Zheng

Hanna Zheng