What Is Trump Trying to Do to the Fed?

A Redefinition of a Century-Old Power Boundary

Introduction

In August 2025, the air in Washington D.C. is thick with the acrid smell of gunpowder.

On the morning of the 12th, President Trump, as is his custom, ignited a news cycle on social media. This time, he announced he was considering a "major lawsuit" against Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell, citing the ballooning renovation budget for the Fed's headquarters, which had surged from an initial $1.9 billion to $2.5 billion. However, it's an open secret that Trump's real frustration is with Powell's monetary policy, which he has criticized for being "too slow to cut interest rates" and for causing "incalculable damage." He even publicly labeled Powell a "loser" and "extremely incompetent"—seemingly forgetting that it was he who appointed Powell as Fed Chair in 2017.

Capital markets reacted instantly: the 10-year U.S. Treasury yield quickly erased its drop and turned upward, and capital flows tightened like sharks smelling blood. The logic for traders was simple: if a president starts directly interfering with central bank decisions, interest rates will no longer be a function of economic data, and political considerations will become the new variable. This not only means a surge in policy uncertainty but could also redraw the risk premium curve for the U.S. dollar.

The showdown between the White House and the Fed is a clash of personalities and a head-on collision of two governing philosophies. At congressional hearings, Powell maintains the composure of a technocrat, repeatedly emphasizing the central bank's dual mandate—maximum employment and price stability. Trump, meanwhile, is accustomed to demanding immediate results with an incendiary, command-and-control style. He argues that the president should hold the central bank directly accountable and, if necessary, pull monetary levers to match the political rhythm.

This latest round has not only torn a new rift in the century-old dam of Fed independence but has also sent a shiver through the markets: future monetary policy may be determined more by the political heartbeat in the Oval Office than by the economic models in the Marriner S. Eccles Federal Reserve Board Building.

The gunpowder smell of August has drifted from the White House to Capitol Hill and has seeped into the nervous system of global financial markets.

Chapter One: The Institutional Firewall, Legacy of the Century-Old Fed

The Federal Reserve was not an abstract concept; it was a central hub forged out of repeated financial crises. Its gene for independence is deeply rooted in the American political philosophy of checks and balances, designed to transcend short-term political cycles and provide an institutional firewall for monetary and credit stability.

From Financial Anarchy to Institutional Catalyst

Before the signing of the Federal Reserve Act in 1913, the U.S. financial system was largely in a state of "wild growth." From 1873 to 1907, several nationwide bank runs led to the collapse of hundreds of banks, wiping out the life savings of ordinary people. The crisis of 1907 was the final blow to the old order. At the time, the U.S. economy was in a golden age of rising industries like railroads, electricity, and automobiles. Trust companies were mushrooming, pouring huge amounts of public funds into the stock market and high-risk bonds. By 1906, half of New York's bank loans were tied up in the capital market, and the bubble was as fragile as thin ice.

A series of black swan events followed—the Boer and Russo-Japanese Wars drew European capital away, and the San Francisco earthquake devastated the West Coast economy. The final fuse was a panic-fueled bank run on the Knickerbocker Trust Company, New York's third-largest trust company, after a failed bid for United Copper Company. The panic quickly spread throughout the entire financial system. Trust companies were the "shadow army" of the banking industry, daring to invest in high-risk assets that banks wouldn't touch. With no central bank at the time, J.P. Morgan almost single-handedly assembled a coalition of bankers, injecting capital into failing institutions and buying up bonds and stocks, acting as a "temporary central bank." For those two months, Morgan was effectively a "one-man Fed." The crisis was quelled, but it exposed a crucial truth: the market needed an institutionalized "lender of last resort" and could not always rely on private prestige and charitable bailouts.

The lesson of 1907 led to a rare consensus among political and financial elites—the market's "self-healing" could not always happen before a systemic collapse. In November 1910, Senator Nelson Aldrich secretly convened key American financial figures on Jekyll Island, Georgia. The group included senior J.P. Morgan & Co. partner Henry P. Davison, National City Bank President Frank A. Vanderlip, and Kuhn, Loeb & Co. partner Paul Warburg—most of them overlapped with Morgan's inner circle in New York finance. The "Aldrich Plan" they drafted drew on the European central bank model but intentionally embedded a system of decentralized power to prevent the central bank from being monopolized by political or financial oligarchs. Attendees traveled under pseudonyms, claiming they were on a "duck hunting trip," a necessary strategy to avoid public backlash and advance financial reform in the political climate of the time.

Institutional Formation and the Design of Independence

On December 23, 1913, Woodrow Wilson signed the Federal Reserve Act, establishing a decentralized structure of a central Board of Governors plus twelve regional Federal Reserve Banks to balance public oversight with banking participation. Board members were given 14-year terms that would overlap multiple presidential administrations, insulating them from short-term political pressure. This design bypassed the semi-private stage of early European central banks. The Fed was a government agency from the start, and while the twelve regional Reserve Banks were non-profit corporations, their stock could not be sold or mortgaged. It was more like an "institutional membership pass" than a capital stake, with their function being participation and oversight rather than profit distribution.

The Fed's highest policymaking body, the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC), consists of the seven governors and five of the twelve regional Fed presidents (the New York Fed president is a permanent member, while the others rotate). This ensures that no single group can manipulate monetary policy. The misconception that the Fed is a "private company" is widespread in some circles, but the reality is the opposite—the core purpose of this two-tiered structure is to prevent control by a few political or financial elites. The danger of this false perception is that it fuels conspiracy theories, erodes public trust in the central bank's independence, and thereby opens a door for political interference.

Theoretical Criticism and Its Legacy

Even with these safeguards, the Fed's independence has always faced scrutiny from academia and the market. In his 1974 Nobel Prize lecture, "The Pretense of Knowledge," Friedrich Hayek criticized the overconfidence of central bank and treasury economists, who he saw as "absurdly" believing they could solve complex issues like employment, income inequality, and productivity simply by adjusting the money supply. Hayek emphasized that the essence of money is credit and its function is merely to reduce transaction costs. He called the government's monopoly on minting currency "the largest-scale robbery in human history" because it allows for arbitrary money printing to pay off debts, leading to currency instability and disordered debt relations. He advocated for the denationalization of money, allowing free competition, and believed that gold would prevail in such a system.

Steve Forbes holds a similar position, arguing that many problems, including the 2008 financial crisis, were caused by the Fed's "blunders," much like its tight monetary policy in 1929 led to the Great Depression. In his view, the Fed is essentially no different from a Soviet-style central planning agency—both wrongly believe that specific policies will yield predictable results, which is precisely what Hayek called the "pretense of knowledge." This criticism goes to the very theoretical foundation of the central banking model, questioning whether its overconfident market intervention might create greater distortions and inequalities.

Through a century of storms, the Fed was born from the ruins of financial panic and established itself on the principle of independence. Yet, it has always maintained an oscillating power boundary amid political clamor and theoretical challenges.

Chapter Two: The Love-Hate Relationship Between the White House and the Central Bank

In American political history, the relationship between the president and the Fed has rarely been one of "mutual success." It is more often characterized by "testing," "resistance," and "conflict." While the theoretical foundation of central bank independence is solid, it often appears fragile in the face of the political realities of power—especially when the White House needs economic data to win votes.

Nixon and Burns: A Classic Case of Political Interference

Before the 1972 election, President Nixon's private phone calls repeatedly came into Federal Reserve Chairman Arthur Burns's office—a back channel known only to the two of them, with no written record. Nixon's intention was clear: to loosen monetary policy and "heat up" the economy before the election to avoid repeating his 1960 loss to Kennedy.

In one call, Burns told the president he had already lowered the discount rate to 4.5% and was prepared to push for more aggressive easing at the FOMC. Nixon said "good" three times, encouraging Burns, "You can lead them... Now, go kick them in the butt."

The combination of loose monetary policy and fiscal stimulus ultimately created the most intractable monster of the 1970s U.S. economy: stagflation—the coexistence of high inflation and economic stagnation. This period became a cautionary tale of monetary policy succumbing to political pressure.

Nixon and the Gold Standard: A Turning Point for the Global Monetary Order

Of greater historical significance was the summer of 1971. The dollar was still pegged to gold ($35 per ounce), and other currencies were pegged to the dollar, forming the Bretton Woods system. However, the "Triffin dilemma" had become apparent: for the dollar to serve as the global reserve currency, it had to be continuously supplied to satisfy international demand, which would inevitably lead to trade deficits and a loss of gold reserves.

To maintain economic growth and avoid tightening monetary policy before the election, Nixon unilaterally announced the closing of the gold window—the dollar would no longer be convertible to gold. This gave the Fed greater policy flexibility but severed the "anchor" of currency issuance. It freed the printing of money from the constraint of gold reserves, opening the floodgates for decades of monetary oversupply, inflation, and asset bubbles.

Carter and Reagan: Tolerance and Conflict

In the late 1970s, the U.S. was mired in an inflation spiral. Despite his dissatisfaction with high interest rates, President Carter appointed Paul Volcker as Fed Chairman. Volcker immediately implemented an unprecedented tightening—the federal funds rate soared to 19%. The housing and manufacturing sectors froze, and unemployment skyrocketed, but the beast of inflation was finally put back in its cage.

After taking office, Reagan publicly supported Volcker but privately explored changing the Fed's decision-making mechanism, hoping it would be more accommodating to the president's economic agenda on interest rates. This tactic of "public support, private pressure" has been repeated in interactions between presidents and the Fed, confirming that presidents tend to seek short-term remedies during economic hardship, while central bank independence proves its value in solving long-term chronic issues.

Obama and Bernanke: A Boundary Breakthrough in Crisis

When the 2008 financial crisis erupted, the Fed, led by Ben Bernanke, launched quantitative easing (QE)—the large-scale purchase of U.S. Treasury securities and mortgage-backed securities to directly influence long-term interest rates. This unconventional operation expanded the central bank's toolkit and ballooned the Fed's balance sheet to an unprecedented size. While QE stabilized the markets, it triggered a long-running debate about its side effects and the timing of its withdrawal.

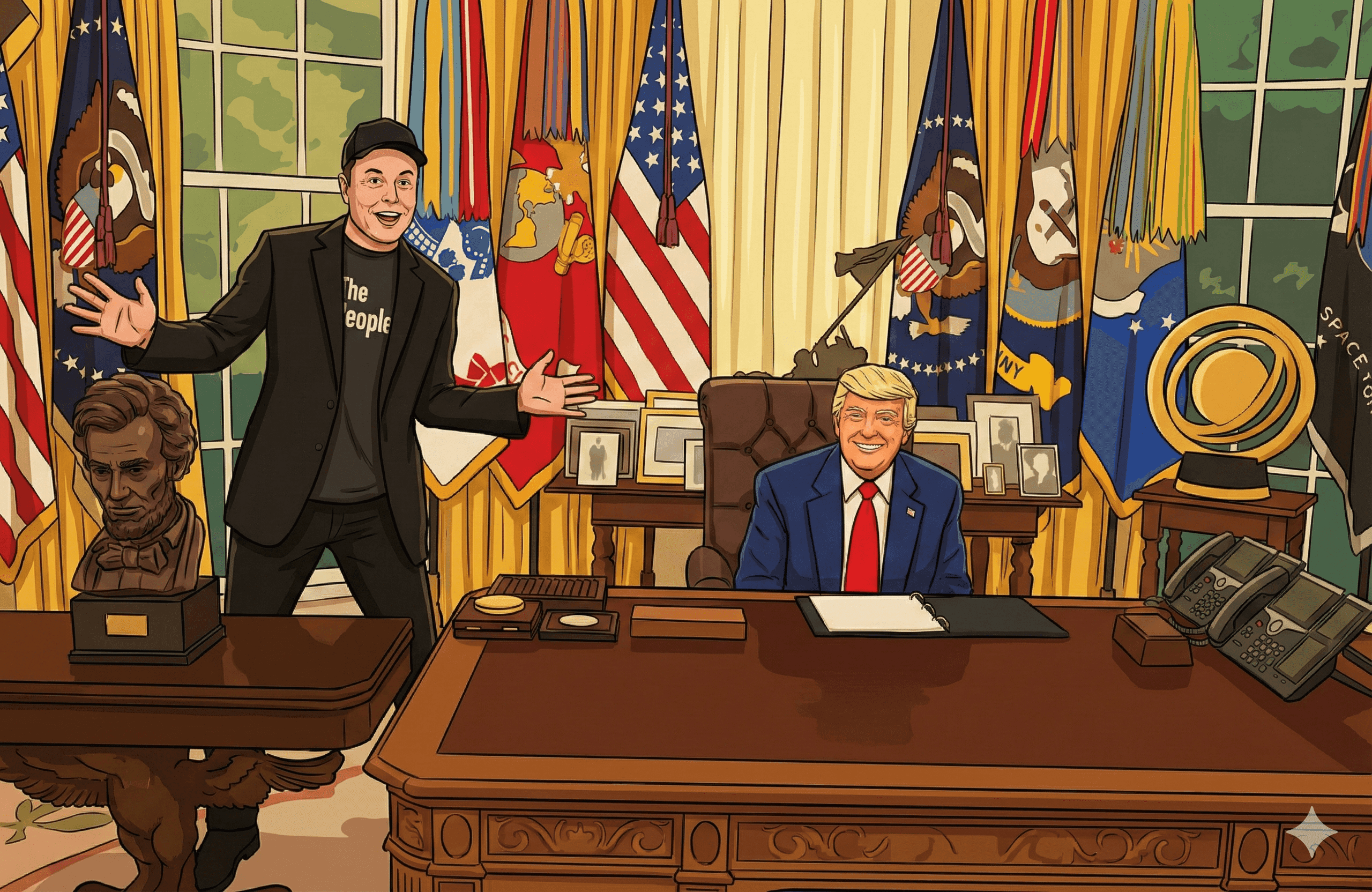

Trump and Powell: The Peak of Open Conflict

After taking office, Trump continued the White House tradition of pressuring the Fed, but in a more direct and personal manner—criticizing by name on Twitter, pressuring through media interviews, and hinting at policy direction in speeches. He demanded that Powell quickly cut interest rates to stimulate the stock market and the economy, bringing monetary policy openly into the political arena. This transformed "central bank independence" from a polite game among elites into a social media brawl.

This history of love and hate demonstrates that Fed independence is not guaranteed by legal text alone; it is a dynamic balance maintained through repeated political shocks. There is an inherent tension between the president's short-term political cycle and the central bank's long-term economic goals. Once the political winds are strong enough, this tension can turn into direct intervention. The result is sometimes a painful lesson in stagflation, and at other times, a drastic reconfiguration of the global monetary landscape.

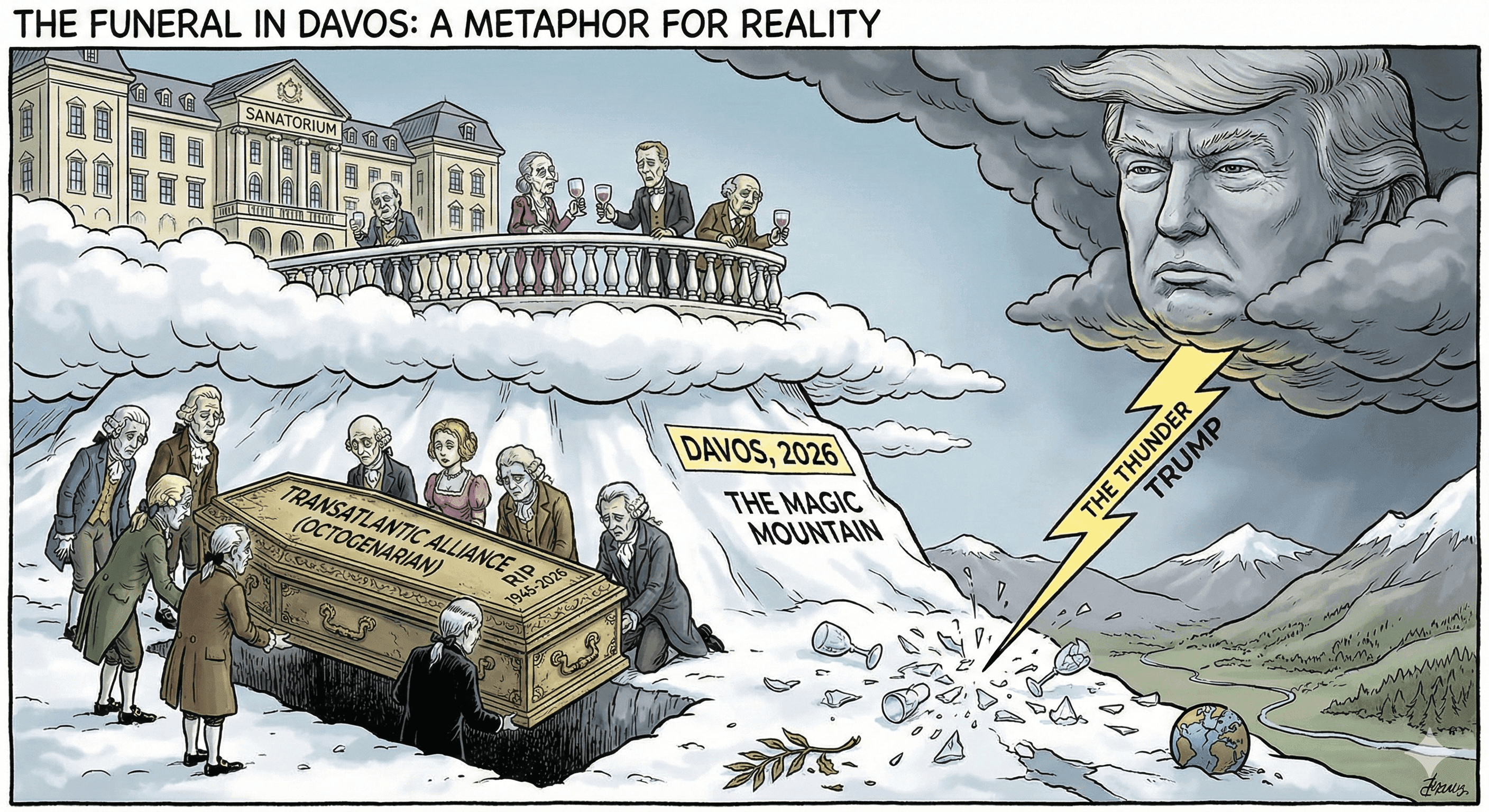

Chapter Three: Trump's Second Act—From Shouting to Surgical Intervention

If Trump's first term was about "shouting at the central bank's doorstep," his second term's intervention has escalated from a "war of words" to "institutional surgery." The cuts are precise, aimed directly at the independent nerve of the century-old central bank.

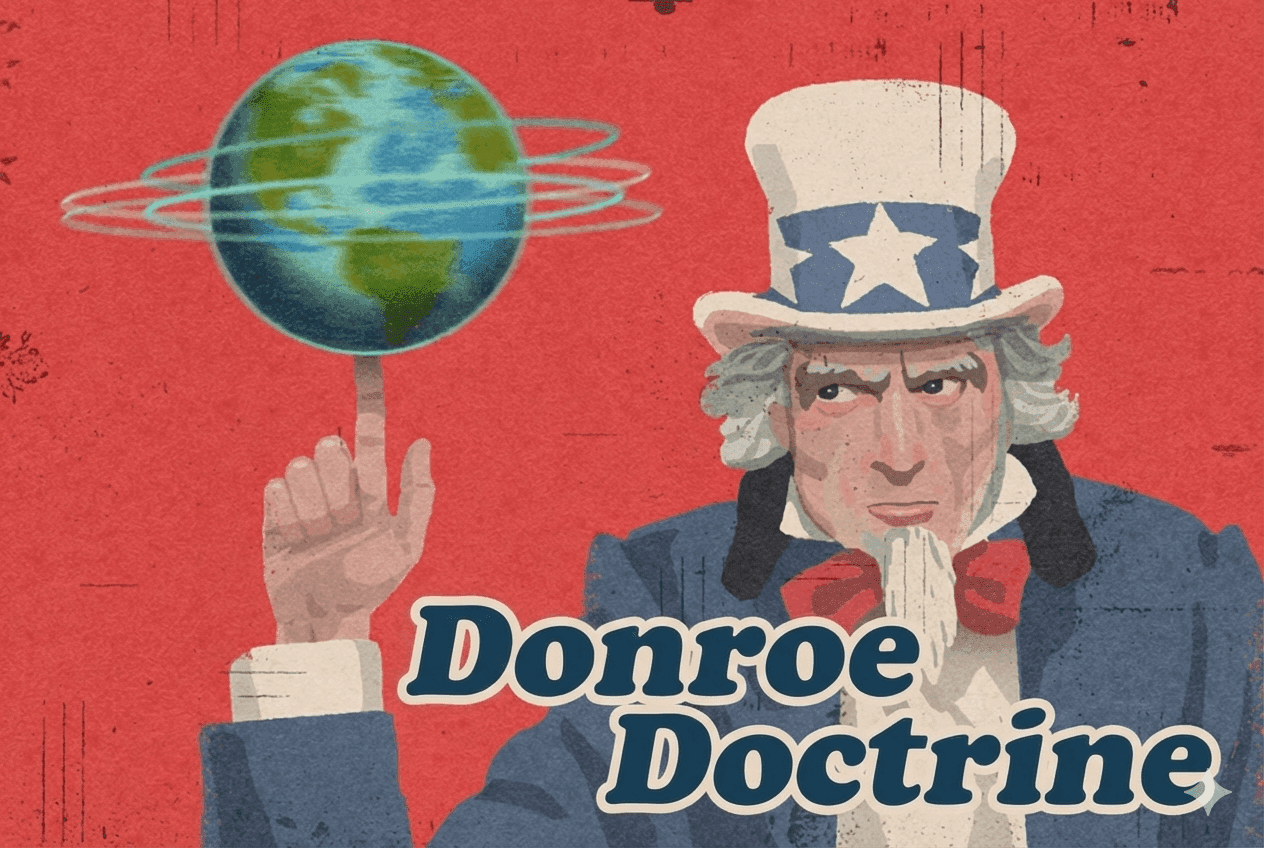

In Trump's view, bringing the Fed under stronger political accountability is the monetary regulatory chapter of his "America First" agenda. The policy framework from Mar-a-Lago emphasizes that the national machinery must serve "Americans" first, not the abstract "global market." This logic, when extended to monetary policy and the regulatory agenda, means bringing them as close to the White House's reach as possible, rather than leaving them entirely to technocrats in insulated institutions.

Executive Order: Eliminating Value Judgments in Finance

On August 7, 2025, Trump signed the "Fair Banking Services for All Americans" executive order. The document's inflammatory nature is clear—it requires federal regulatory agencies to conduct a 120-day retrospective review and impose fines or refer to the Department of Justice any instances of "political or illegal debanking." It explicitly prohibits regulators from using the vague standard of "reputational risk" to cut off financial services to specific industries or groups (such as firearms, energy, cryptocurrencies, and religious organizations).

This was not an arbitrary move but a response to long-standing complaints from conservatives about the "infiltration of woke culture into the financial sector." Several high-profile recent cases provided Trump with political ammunition:

* JPMorgan vs. The National Committee for Religious Freedom (NCRF): A new account opened by the NCRF, led by former Kansas Governor Sam Brownback, was abruptly closed in 2022, and the organization was asked to disclose its donor list. While JPMorgan insisted there were "red flags" during the account opening and that the NCRF failed to provide necessary documents, conservatives saw it as clear evidence of religious discrimination.

* WePay Terminating a Conservative PAC's Ticket Sales: In 2021, WePay, a JPMorgan subsidiary, terminated ticket sales for a Missouri conservative political action committee, "Freedom Defense," citing a "potential terms of service violation," forcing the event to be canceled. Although the service was restored under public pressure, the incident became a classic example cited by conservatives.

* Trump's Personal Grievances: He claimed that several large banks, including JPMorgan and Bank of America, refused to accept his deposits exceeding $1 billion, forcing him to split the funds among multiple smaller banks. (This claim has not been publicly substantiated by the banks or official documents.)

The political syntax of the executive order is clear: to shift the basis of bank decisions from subjective "value judgments" back to objective, measurable financial risk standards. This is not just a tweak to regulatory language but a redrawing of the boundaries of financial institutions' social responsibility. In fact, the OCC and the Fed had already announced in March and June that they would stop using "reputational risk" in their examination ratings.

Personnel Appointments: Moving the Pieces

Accompanying the executive order is a more penetrating personnel strategy. Taking advantage of the resignation of Fed Governor Adriana Kugler, Trump nominated Stephen Miran, the Chairman of the White House Council of Economic Advisers, to a governor's seat. He hopes for confirmation before the September FOMC meeting to shift the committee's dynamics while Powell is still in office. Miran is seen as an advocate for a more "rules-based, pre-emptive easing" approach.

Stephen Miran had already proposed a reform plan in March 2024, which included six key points:

1. Strengthen political accountability: Shorten governors' terms, ban the "revolving door" between the executive branch and the Fed, and empower state governors to make appointments, giving regional Fed banks a larger role in monetary policy votes to balance the White House's control over the Board of Governors.

2. Strip politicized functions: Transfer highly politicized functions like credit allocation and bank supervision to a new institution created by the president, aligning them with fiscal policy.

3. Optimize decision-making: Separate the chairman's role from a CEO function to prevent groupthink, ensure each member's responsibility and influence are equal, and promote a diversity of opinions.

4. Create a crisis-response vice chair position: This person would be responsible for unconventional tools when the president declares a financial emergency, with a limited term and subject to congressional renewal.

5. Enhance democratic legitimacy: Through the nationalization of Reserve Banks and local governor appointment mechanisms, increase the democratic legitimacy of the Fed system.

6. Emphasize gradual implementation: Avoid market shocks by pre-announcing personnel changes and phasing in new dismissal powers.

The overall goal is to weaken excessive independence and introduce political and democratic oversight, making the Fed both technically functional and more accountable and legitimate.

Meanwhile, Treasury Secretary Besant stated in a recent television interview that if the Bureau of Labor Statistics had more promptly corrected its employment data, the interest rate cuts in June and July could have happened sooner, leading to a one-time 50-basis-point cut in September and entry into a "continuous easing corridor" of 150-175 basis points. He said this reflected a correction for "prior excessive tightening," not a judgment of recession.

Trump has nicknamed Powell "Too Late" because he believes the Fed chair is slow to react on monetary policy, unlike a more forward-looking Greenspan. Besant believes the U.S. economy is returning to its 1990s state, which requires more proactive policy, whereas Powell is overly reliant on "data-driven" decisions rather than anticipating trends. Besant also criticized the Fed for overstepping its authority in regulatory matters, "stepping on the toes of other regulators," and reminded it that it is only one of three major bank regulators.

In addition to personnel changes, the Trump team has sent three layers of signals:

* Internal political cleansing: They criticized a resigning governor for publicly calling for rate cuts during Kamala Harris's campaign, which they saw as weaponizing monetary policy. Besant jokingly said he couldn't tell if this was "TDS" (Trump Derangement Syndrome) or "Tariff Derangement Syndrome."

* Vice-chair suspense and "list politics": They are noncommittal on whether they will keep the current vice chair and are floating potential private-sector candidates in batches, using a "rolling appointment-rolling pressure" strategy—first promoting "market-oriented" candidates, then adding "institutionalists."

* The "shadow chairman" concept: Before Powell's term expires in May 2026, they might create a quasi-cabinet role to guide the path of interest rates and regulatory policy, pre-emptively stripping him of his policy leadership.

The Congressional Path: An Extension of the Legislative Front

Trump knows that executive orders are fast but have limited scope. What can truly reshape the central bank's power is legislation. He is pushing Republican lawmakers to enshrine ideas like central bank transparency and asset size constraints into law as a long-term "headache" for the Fed. A bipartisan audit proposal is seen as a breakthrough, which could force the Fed to hand over more of its decision-making drafts and operational records to Congress and the public.

Trump is less concerned with the fine print than with the pace of the agenda and its symbolic meaning: limiting the balance sheet and restricting unconventional tools are all institutional checks to pull the central bank back from "spinning on its own" to "spinning in sync." As for extreme ideas like returning to the gold standard or abolishing the dual mandate, he is content to let his think tanks and media outlets promote them, creating leverage for negotiations with Congress, even if they aren't immediately implementable.

The Fed's fortress of independence won't crumble overnight, but each of Trump's cuts is rewriting the invisible power boundary of the last century—making monetary policy more like an extension of the White House's economic agenda rather than a technocratic project kept at a "respectable distance." Even if the reforms are diluted, he wants to leave his mark in history books and party memory as the "president who rewrote the financial constitution."

Some outsiders interpret this "power grab" as an attempt to replicate a Russian-style central bank and state capitalism, but this is a misunderstanding. Trump is focused on what he sees as the U.S. being "short-handed" and "slow to react" in the global arena. In his eyes, many countries can use their state machinery to pave the way for their businesses, while the American president is often hamstrung by layers of institutional constraints. What he wants to advance is a version of "expanded executive power," not a simple dictatorial impulse.

Chapter Four: Congress's Calculation and The Game

In the chess match of Fed reform, Congress is neither a silent spectator nor the sole manipulator. It is more like a cautious dice thrower—one hand holds the consensus chip of "transparency and accountability," while the other weighs independence against control. The differences between the two parties on central bank power are not as clear-cut as on issues like immigration or taxes. They may seem at odds publicly but often find surprising common ground in private.

Rare Bipartisan Consensus

Whether Republican or Democrat, virtually no member of Congress would publicly oppose "increasing Fed transparency and accountability"—it's a form of American political correctness.

During the 2008 financial crisis and the COVID-19 pandemic, the size and speed of the Fed's unconventional monetary policies left Congress feeling in the dark. Issues like emergency lending conditions and the rapid expansion of the balance sheet touched a nerve. The Fed Transparency Act (H.R. 24) is a product of this consensus, requiring the Government Accountability Office (GAO) to conduct a "full-scope audit" of the Board of Governors and the twelve regional Fed banks within a year, covering the decision-making chain, asset purchases, and the use of emergency tools. This is not just a technical reform but a political declaration by Congress to "reclaim some oversight"—a reminder to the Fed that independence does not mean being unaccountable.

The Republican "Power-Grab" Faction

Conservative Republicans—especially those influenced by the "Project 2025" agenda—are inclined toward more fundamental reforms, not only tightening transparency but also weakening the Fed's discretionary power over its tools, size, and mandate:

* The Scott Plan: Senator Rick Scott's proposal would cap the Fed's total assets at 10% of GDP, ban it from holding MBS and long-term Treasury bonds, and limit the duration of emergency loans, requiring congressional approval for any extension beyond one year.

* Extreme Ideas: Even more right-leaning voices advocate for a return to the gold standard, abolishing the "dual mandate," and keeping only price stability, with some even questioning the need for the Fed's existence.

The core logic of these proposals is a belief in free markets—the more the central bank intervenes, the greater the market distortion. It's better to let the market set prices than have technocrats in charge.

The Democratic "Stability" Faction

While Democrats support audits and transparency, they still view the Fed as an "institutional firewall" in times of crisis and are reluctant to see it directly co-opted by Congress or the White House. Their priority is risk prevention: strengthening capital requirements for large banks, increasing stress tests, and improving macro-prudential regulation, rather than cutting the Fed's overall power.

However, on non-ideological issues, Democrats will cooperate with Republicans. For example, on reforms to the Supplementary Leverage Ratio (SLR), a bipartisan group led by Representative Andy Barr called for adjustments to improve liquidity and resilience in the Treasury market. This type of technical fix neither threatens the central bank's independence nor garners bipartisan support.

Checks and Balances or a Takeover?

The Republican calculation is to use legislation to move the monetary policy faucet back to Congress. The Democrats, meanwhile, are defending the Fed's space for crisis response, preventing both presidential overreach and Congress from tying the central bank's hands. This dual mindset means Congress could either be an enabler of Trump's reforms or a stumbling block at a critical moment. If a bill touches on core party or constituent interests, a position reversal can happen faster than expected.

Congress, in the context of Fed reform, is not merely a check on power. It is a political institution that both wants more power and fears a breakdown. Every move it makes can alter the balance of the game. In the gaps where the two parties' calculations intersect, central bank independence could either be chipped away slowly or temporarily preserved. In other words, the Fed's future depends not only on the will of the White House but also on whether Congress pushes or pulls.

Chapter Five: Powell and the Fed System's Defensive Strategy

Facing a two-front offensive from the White House and Congress, Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell has chosen the most traditional and difficult defensive path in American central bank history—neither confronting them head-on nor giving ground easily. He seeks to defuse the shock through institutional buffering and by controlling the pace.

Institutional Defenses: Decentralization and Independence

Powell's confidence comes from the institutional firewalls embedded in the Fed's constitutional and financial system:

* Collective Decision-Making: The seven Board members and five of the twelve regional Fed presidents vote together. The president cannot directly dismiss most of them, making it difficult for a single political force to control the outcome.

* Staggered Terms: The 14-year terms for governors naturally cross political cycles.

* Financial Independence: The Fed's operations are funded by its asset earnings, not congressional appropriations, which reduces the risk of budget-based leverage.

While this system is not perfect, it gives Powell room to maneuver.

Internal Rifts: Unity and Cracks

There are ideological differences within the Fed on regulatory policy:

* Deregulation Faction: Governor Michelle Bowman, for example, advocates for relaxing the capital and liquidity requirements strengthened after 2008 to reduce compliance costs and unleash credit, a stance that aligns with the Trump administration's deregulation agenda.

* Prudential Faction: This group emphasizes learning from the 2008 crisis by reinforcing capital buffers during stable economic periods to prevent systemic risks from being amplified during a crisis.

These divisions could be a critical difference in votes, and if the White House exploits these cracks, the defensive line could weaken.

Psychological Warfare: Playing for the Second Half

Powell's implicit goal is to hold out until his term expires in May 2026. At that point, a change in the congressional landscape, presidential approval, or economic conditions could naturally alleviate pressure on the central bank.

Volcker used a similar "technocratic defense" against Reagan in the 1980s, and Greenspan against Clinton in the 1990s. But in the era of social media and the 24/7 news cycle, maintaining this restraint is a high-stakes psychological battle.

The Fed was designed from its inception to be a "slow, decentralized, and consensus-driven" machine. Its astute founders understood the workings of the American system, using "redundancy and mutual veto" to counter everyone, including the president. In reality, even replacing Powell would not mean an immediate change in the decision-making mechanism. You can adjust the boundary conditions, but it's hard to override the institution itself.

Chapter Six: The Dual Lenses of Economics and Political Science

The conflict between the central bank and the White House, while appearing to be a power struggle, is fundamentally intertwined with two academic concepts: time inconsistency and public choice theory. It is an endless tug-of-war between short-term stimulus and long-term stability, and it reflects the profound social restructuring effects of monetary policy through the Cantillon effect.

Time Inconsistency: The Mismatch Between Political Cycles and Policy Goals

The economic theory of time inconsistency states that policymakers face a mismatch of incentives at different points in time:

* Short-term temptation: During an economic downturn or approaching an election, loose monetary policy can quickly lead to rising employment, a booming stock market, and increased confidence.

* Long-term costs: Excessive easing can drive up inflation, accumulate debt, and fuel asset bubbles.

A president is naturally driven by a four-year political cycle, seeking immediate economic results. The central bank, however, prioritizes long-term stability, even if it means short-term pressure. Consequently, at critical moments, the White House and the Fed often find themselves in opposing positions.

Nixon's pressure in 1972, Carter's tolerance of high interest rates, and Trump's calls for rate cuts are all different versions of this mismatch—the only difference is that the pressure has evolved from backroom conversations to globally broadcast Twitter politics.

Public Choice Theory: The Central Bank Is Not a Disinterested "Deity"

Public choice theory reminds us that while the central bank is independent, it is not transcendent. Fed governors and regional Fed presidents are also driven by their reputations, careers, and policy legacies. In a crisis, the tendency to expand their toolkit and balance sheet often creates an internal conflict with the goal of maintaining long-term stability.

This "self-interest" can sometimes provide a buffer against political interference (losing independence would mean a loss of their own authority). But when external pressure is strong and internal divisions deepen, it can also accelerate the central bank's alignment with political power.

The Cantillon Effect: The Hidden Redistributive Consequences of Monetary Policy

The Cantillon effect reveals that new money flows first to financial institutions, large corporations, and asset holders, who can acquire assets at a lower cost before prices generally rise. Ordinary wage earners only feel the impact after prices have already gone up—their purchasing power decreases without a corresponding increase in income. As a result, wealth becomes concentrated in the hands of capital holders, and the wealth gap widens.

Thus, monetary policy is never a value-neutral "technical operation" but a political-economic tool that redistributes wealth and opportunities within society. This fact is being leveraged by populist politicians who paint the central bank as a technocratic institution that "only works for Wall Street," finding a moral justification for political intervention.

The conflict between the White House and the Fed is a reflection of the ideal models of economics clashing with the real-world logic of political power, causing the issue of the Fed's "independence" to cycle back to the center of public and legislative debate. It repeatedly validates the applicability of time inconsistency and public choice theory, and it constantly tests whether the institution can maintain a balance between temptation and restraint.

Chapter Seven: Three Scenarios for the Future—Independence, Expanded Power, and Checks and Balances

Trump's Fed reforms are not just a debate over monetary policy. They are like a chisel blow to the foundation of the American financial constitution. The outcome could lead to three paths—a marginal erosion of independence, an acceleration of presidential power, or a system of checks and balances between Congress and the president—each of which would reshape the economic lives of ordinary people.

Scenario One: Marginal Erosion of Independence (Baseline Scenario)

Probability: Medium to High

Characteristics: Limited political interference, with the central bank retaining its core autonomy but becoming more sensitive to signals from the White House and Congress at the policy margins.

In the most likely scenario, Trump's reforms will achieve limited but substantive results, and the Fed's core independence will be preserved. Executive orders will be fully implemented, and regulatory standards will shift. Parts of the audit and tool-restricting legislation, such as the Fed Transparency Act (H.R. 24), may pass.

Personnel changes will increase the White House's influence on interest rate policy, but the Fed's collective decision-making mechanism and long-term term structure will continue to act as a firewall against excessive political interference.

Impact on the public: Banks will no longer easily deny customers based on political labels, religious beliefs, or industry sensitivity (firearms, cryptocurrencies, etc.). Small businesses and sole proprietors will have easier access to financial services. However, interest rates might carry a slight "political premium," causing mortgage and car loan costs to rise by a few percentage points, and some families may postpone buying a home or a new car. Inflation expectations will rise slightly, and the purchasing power of savings will be moderately affected. Overall, it will be a "boiling frog" environment where risks are manageable and the economy remains stable.

Scenario Two: Accelerated Presidential Power (Downward Risk)

Probability: Low to Medium

Characteristics: The Fed bows to the president's will on key policies, its independence becomes a sham, and monetary policy becomes short-term and politicized.

Trump not only pushes for reform but also rewrites the central bank's power boundaries—gaining the authority to dismiss governors and regional Fed presidents, transferring budget and some regulatory power to the Treasury Department, and appointing a highly aligned, dovish chairman.

As a result, the Fed rapidly cuts interest rates, and the floodgates of monetary easing open wide, weakening the internal checks and balances.

Impact on the public: In the short term, corporate borrowing will be active, the stock market will be euphoric, and employment data will look great. But within a few years, inflation could soar like it did in 1990s Argentina. The value of people's savings will evaporate faster, hitting low- and fixed-income individuals the hardest. The cost of living will skyrocket, and the prices of milk and eggs on supermarket shelves might be updated monthly. Asset market bubbles will build up, and ordinary investors will take on more leverage in a bull market illusion, increasing risk dramatically. When the next economic downturn arrives, the loss of Fed independence will strip it of its flexibility as the "lender of last resort," amplifying economic volatility and increasing job and income uncertainty.

Scenario Three: Checks and Balances Between Congress and the President (Upward Risk)

Probability: Medium

Characteristics: Reforms are blocked, and independence is preserved through institutional and political maneuvering. The Fed remains the world's most credible central bank.

In this ideal but difficult-to-achieve scenario, Congress and the judicial system block radical reforms. The legislature insists on oversight but preserves monetary policy autonomy, and the market's risk pricing for political conflict returns to rationality.

The Fed continues to gradually adjust policy under the guidance of technocrats, maintaining the stability of its long-term goals.

Impact on the public: In this scenario, families and businesses can plan in a predictable monetary environment. Inflation and employment are managed in a balanced way, asset market risks are controlled, and the Fed retains enough tools to backstop the economy during a crisis. Although short-term stimulus may be limited, long-term stability is the best guarantee for people's livelihoods: job opportunities are sustained, living costs are manageable, and savings are more secure. The existence of central bank independence at critical moments is like an insurance company that actually pays out on a policy—it's not needed every day, but it can be a lifesaver during a financial storm.

These three scenarios are not mutually exclusive; they could overlap and shift in reality.

No matter which path is taken, Fed independence is the key piece on the board. It affects not only Wall Street's asset curves but also every household's loan agreement, paycheck, and supermarket bill. For the average American, this seemingly abstract institutional struggle could determine the thickness of their wallet and their future stability. And if the dollar's dominance is shaken, global capital flows will be reshuffled, and emerging markets and dollar-dependent countries will feel the shock.

The Echoes of History

Trump's reforms of the Fed are the latest echo in a two-century-long power struggle between the White House and the central bank. It is also a high-stakes gamble to redraw the dollar system and the global financial map.

Looking back at American history, the clash between presidents and central banks has never been a gentle debate but a series of hard-hitting confrontations that have reshaped institutions: In the 1830s, Andrew Jackson "killed" the Second Bank of the United States, cementing the American DNA of opposition to centralized financial power. In 1971, Richard Nixon unilaterally ended the dollar's convertibility to gold, terminating the Bretton Woods system. This gave the Fed unprecedented policy freedom but also sowed the seeds of inflation and asset bubbles.

Today, Trump not only continues the tradition of "pressure" but, for the first time, is using institutional surgery, attempting to reshape this century-old line in the sand through law, structure, and personnel. He wants to make monetary policy not a technical project behind high walls but a direct extension of the Oval Office. Behind this is Trump's triple helix of motivation: a personal grudge turning into institutional revenge, an electoral calculation becoming a long-term strategy, and a historical ambition driving him to test the boundaries of the financial constitution. And this boundary has never been an inscription carved into the marble of the constitution but a coastline that drifts with political maneuvering, economic cycles, and capital flows.

How far Trump can go depends not only on which side Congress stands on but also on whether the market's patience and trust can hold the line. History's verdict is harsh: once the market loses patience, it doesn't need to vote—a single sell-off can tip the scales of power.

Will the next storm be in a few years, or before the next FOMC meeting? No one can give a definitive answer. But one thing is certain: this time, the whole world is tied to the same boat.

Ting Tang

Ting Tang Stephany Yu

Stephany Yu