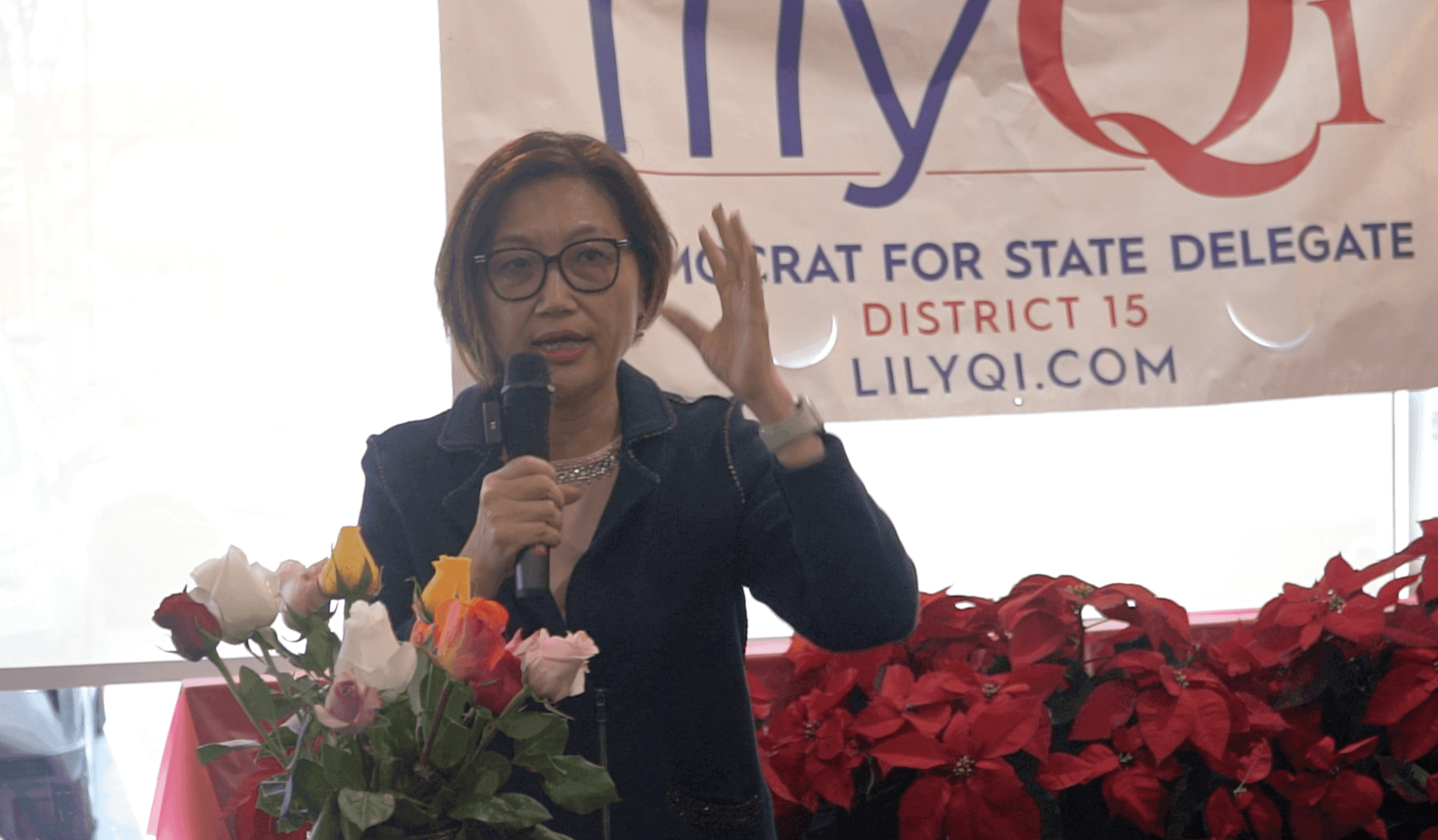

Grassroots Asian Americans Mobilize to Boost Turnout for Election

Twenty-two Chinese Americans traveled by bus from the Washington metropolitan area to Philadelphia on the second Saturday of October. They weren’t visiting landmarks like the Liberty Bell or the birthplace of the Constitution—they were out to actively uphold their belief in the Constitution by canvassing for the candidates they trusted.

22 Chinese Americans traveled to Philadelphia, canvassing for Democratic presidential nominee Kamala Harris. Photo Credit: Chao Wu

The group’s goal was to go door-to-door, talking to Democratic and Independent constituents to ensure they went to the polls or mailed in their votes for Democratic candidates across the board, especially presidential nominee, Vice President Kamala Harris. In Pennsylvania, a state whose razor-thin margins have determined winners in the past two election cycles, every vote could make a difference.

Meanwhile, another group of Asian Americans—including Chinese, Vietnamese, and Thai Americans—canvassed outside Asian grocery stores in Northern Virginia, working to encourage support for Republican candidates in both local and presidential races, even within this predominantly blue district. They assisted seniors with limited English proficiency in registering to vote, ensuring their participation in the upcoming general election in November.

Trump's Chinese American supporters rallied with large banner. Photo Credit: Sarah

At Eden Center in Falls Church, Virginia—a strip mall that Trump visited in late August—the group set up a station originally intended as a place for passersby to rest or chat with neighbors from the community. Now, it had been transformed into a political campaign station, draped in flags and signs, and surrounded by loud patriotic music. Every volunteer wore something red, whether MAGA hats or T-shirts featuring the iconic image of Republican presidential nominee Donald Trump raising his fist during the first attempted assassination earlier this summer.

Asian Americans have been the fastest-growing group of eligible voters in the U.S. over the past two decades, according to the Pew Research Center. In the latest survey by AAPI Data and APIAVote, 77% of Asian American voters said they are “absolutely certain” they will vote in the 2024 election—a significant increase from four years ago when less than 60% of eligible Asian American voters turned out. Many within this community are not only committed to voting themselves but are also actively working to motivate others and boost turnout across the political spectrum. Although lacking substantial support and resources from the political parties they actively endorse, grassroots Asian American political campaigns employ inventive strategies to amplify their visibility and impact in the voting landscape.

Traveling to Swing Districts for Canvassing

The group of 22 Chinese Americans, organized by Maryland’s State Delegate Chao Wu, a first-generation Chinese immigrant, came together from diverse backgrounds, locations, ages and even political affiliations. Collectively, they knocked on approximately 3,000 doors, talked to residents, and encouraged them to vote in person or mail in their ballot.

The youngest of the 22 Chinese Americans bused to Philadelphia for canvassing was only ten years old. Photo Credit: Chao Wu

They represented merely a fraction of the burgeoning wave of Asian Americans who recently traveled to Pennsylvania to canvass for Harris. According to Paul Zhu, Co-Chair of “Chinese Americans For Harris” and head of battleground state canvassing efforts, the group organized similar door-to-door canvassing initiatives each Saturday in October and on the first Saturday in November, the last weekend before Election Day.

While not every weekend included free shuttle buses, Asian American Democrats within a three-hour drive of Philadelphia, from areas like the Washington metropolitan area and New York City, were encouraged to make the trip. Additionally, Chinese American volunteers in Philadelphia’s Chinatown offered rest stops and refreshments to support canvassers in their campaign efforts.

Using the “MiniVAN Canvassing” app, volunteers could review households’ voting preferences from previous election cycles before knocking on doors. Their canvassing primarily targeted those who had historically supported Democratic candidates, with the goal of ensuring these voters turned out.

“Turnout is key. Whoever can drive out more voters will win the race,” Zhu said, adding that they preferred volunteers to focus their efforts elsewhere rather than attempting to convert Republicans because “it’s challenging to sway people’s convictions in the final weeks before the election.”

Paul Zhu was interviewed by Yuan Media at home in Fairfax County, Virginia. Photo by: Pingping Yin

Philadelphia is home to an estimated 37,000 ethnic Chinese residents, with approximately 60% being foreign-born, according to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Chinese American canvassers from outside Pennsylvania were especially eager to engage with these residents in their native language to encourage voter turnout.

Besides the organized campaign in Pennsylvania, grassroots Asian Americans also mobilized independently in other battleground states. Among them was Cissy Wang, an IT consultant with the South Carolina state government, who drove to neighboring North Carolina and Georgia every weekend since September to canvass for Harris.

Typically canvassing solo, Wang divided each day into two sessions, morning and afternoon, knocking on 60 to 80 doors per session. To date, she has visited approximately 300 homes across the two swing states. None of the neighborhoods she canvassed were areas with a significant Asian presence, nor were they traditionally Democratic strongholds like Philadelphia.

Cissy Wang knocked on doors in Charlotte, North Carolina to canvass for Harris. Photo by: Jenny Tang

“I’m here to represent the Chinese community and make our presence known,” Wang said. Her goal was to show voters that, although Asian Americans are a minority, they are actively engaged in the political process and deeply invested in the country’s future.

Wang recalled frequently encountering indifference during her door-knocking efforts in these swing states. “Why should I vote? My single vote won’t make any difference,” was the response she heard most often.

“If no one takes action, society will remain exactly as it is,” Wang countered. “Is that truly the outcome you believe is right?” She said, “Without action, the country will never evolve into the place we hope for. Our votes are our voices, and change begins with voting—it’s the simplest yet most powerful action we can take.”

Wang shared her own story, explaining that as a Chinese immigrant from an entirely different political system, she had limited understanding of democratic processes when she first arrived in the U.S. decades ago. Now, deeply involved in political engagement through voting and canvassing, she told them “In this country, everyone has a voice, including us Asian Americans. If you think you’re insignificant and that your voice doesn’t matter, then by staying silent, you become invisible.”

Through her impassioned words, Wang managed to convince a few individuals to commit to voting. Some, initially reluctant to open the door, later invited her inside to warm up or use the restroom, appreciating her dedication.

Cissy Wang(front row, left) and other Democrat volunteers canvassed for Harris near an Asian grocery store in Atlanta, Georgia. Photo by: BiLan Liao

Young Asian generations are also participating in canvassing though some are not yet eligible to vote. The youngest of the 22 Chinese canvassers was only ten years old. “This kind of participation empowers young people to find belonging and responsibility,” said his dad.

Melinda Liu, another minor in the group became interested in politics after the Ukraine War started in 2022. “The issues that hang in the balance of the election today will affect the country I grew up in and will inherit, and I want to live in a country that goes forward, not back,” said the 14-year-old.

Not all young Asians receive full support from their parents in their political pursuits. Victor Nguyen, a high school student in Prince George’s County, Maryland, boldly approached a Democratic campaign station at Eden Center, seeking an opportunity to volunteer for Harris while his parents browsed the Vietnamese vendors. His political and religious ideologies diverge significantly from those of his parents, who are supporters of Trump and the pro-life movement.

Nevertheless, Victor chose to openly express his political views, striving to persuade passersby of why Harris would be a more favorable choice for the Vietnamese community, which predominantly features small businesses displaying political yard signs in support of Trump-Vance.

Victor Nguyen, a 16-year-old high school student in Maryland, volunteered at an Asian American for Harris campaign station in Northern Virginia. Photo by: Pingping Yin

As with any ethnic group, the Asian American community includes supporters of both major political parties. Republican Asian Americans are equally if not more passionate in supporting their candidates.

In mid-October, Mike Nguyen’s Tesla truck stood out among the rallying vehicles in Northern Virginia, proudly sporting four flags, each as tall as an adult male. Three flags displayed his support for Trump-Vance, while the other honored his Vietnamese heritage. He had driven all the way from Little Rock, Arkansas, to Washington, D.C., with his 92-year-old mother as his sole passenger. Together, they stopped at every Trump rally en route to show their steadfast support for the Republicans.

As refugees of the Vietnam War, the Nguyen family still remembers Biden’s 1975 stance as a senator against accepting Vietnamese refugees, a memory that fuels their staunch Republican allegiance. According to Nguyen, his mother, despite her age, is even more fervent in her support for Trump due to her fear of the country moving toward a socialist and communist regime under a Democratic administration. Nguyen said that for her, backing Trump is a part of her final wishes, and as her son, he felt his obligation to help fulfill that.

Unwavering in Ideologically Opposed Districts

Even in states and districts where the majority significantly diverges from their party affiliations, many Asian Americans remain undeterred, fervently advocating for the candidates they believe in.

Among them is Sarah, a passionate Republican Chinese American who preferred not to share her last name for fear of retaliation. Despite residing in a predominantly blue district in Northern Virginia, Sarah and her “patriot” Asian American allies have made considerable efforts to canvass for Trump since mid-August. They set up a campaign station at Eden Center, a bustling strip mall in Falls Church, Virginia, filled with Vietnamese-owned small businesses.

A Trump campaign station was set up by Asian Americans at Eden Center, Falls Church, Virginia. Photo by: Pingping Yin

Positioned outside one of the area’s most well-known Asian grocery stores, the campaign station was surrounded by a sea of Trump-Vance yard signs and flags, where Sarah and her peers distributed multilingual pamphlets in several Asian languages explaining why people should support the Republican Party.

They also provided multilingual sample ballots to spotlight Republican candidates, from the presidential race down to local elections. With Trump’s favorite songs like “God Bless the USA” playing loudly and repeatedly in the background, they assisted senior Asians who have limited English proficiency, guiding them through the voter registration process and patiently addressing any questions in their native languages.

Their station typically wrapped up around 5 p.m.. Immediately after that, they moved to nearby neighborhoods conduct door-to-door canvassing. Drawing on extensive experience, Sarah shared that 5 to 7 p.m. is the ideal time for door-knocking, whether on weekdays or weekends. It’s when people are coming home from work or outings and just starting to plan dinner.

“If you go earlier, they won’t be home; if you go later, it’s getting dark, and people are hesitant to open the door at night. Plus, we don’t feel safe knocking on doors after dark,” Sarah said.

Advocating for Republicans in a solid blue area poses challenges, particularly for ethnic minority groups. Among the flags adorning their station, the most prominent one declared, “Don’t Blame Me, I Vote for Trump.”

Among the flags adorning their campaign station, the most prominent one declared, “Don’t Blame Me, I Vote for Trump.” Photo by: Pingping Yin

At one point, a white man argued with them over Trump’s policy agenda. A Vietnamese elder in the group stepped forward, yelling back: “What about the border? Would you accept leaving your front door open for strangers to enter and live in your home?” The man replied that he’d be fine with it. “In that case, give me your address,” the Vietnamese senior retorted. “I’ll move in tonight!”

Sam Shi, Sarah’s peer Chinese American and a data analyst at Northern Virginia Community College, recounted their participation in the Fairfax County festival in early October, where they donned MAGA apparel and waved Trump flags. Some attendees responded with hostility towards them, raising their middle fingers and hurling insults.

“People hold different ideologies, and that’s perfectly acceptable. However, they shouldn’t resort to cursing us. Such behavior is mean-spirited and rude. We advocate for Trump peacefully, yet we’ve faced threats of violence,” Shi said. “Some even expressed a wish for Trump to die. This serves as a stark testament to the radicalism of Democrats. Truly decent people don’t wish anyone to die.”

Daniel Ding experienced similar hostility while distributing flyers that highlighted Republican agendas in front of Great Wall Supermarket, one of the oldest Asian grocery stores in Northern Virginia.

Ding and his fellow members of the Christian religious community produced bilingual flyers in both Mandarin Chinese and English to break down Republican agendas. After reading their flyers, a few passersby insulted them, calling them idiots and telling them to “go back to China” if Trump were elected.

Daniel Ding was interviewed using the Trump-Vance yard sign as a background. Photo by: Pingping Yin

However, these hostile encounters only strengthened Ding’s resolve. “Their insults and indifference expose just how much the country is collapsing and the urgency to set it right,” he said. Ding saw his efforts as a wake-up call for his fellow Asian Americans.

There was no designated space for a campaign station in that plaza, so Ding and his religious sisters stood by the grocery store’s sole entrance for approximately five hours each day. Many of them, in their fifties, took brief respites in their cars, sipping hot drinks to sustain themselves.

“We are the grassroots among the grassroots without the support of a local Republican organization. Distributing this message is both our duty and our only recourse. Let the politicians do their jobs and address the systemic issues; we will handle the grassroots efforts ourselves,” Ding said, describing himself as a “messenger.”

Campaigning Behind the Scenes

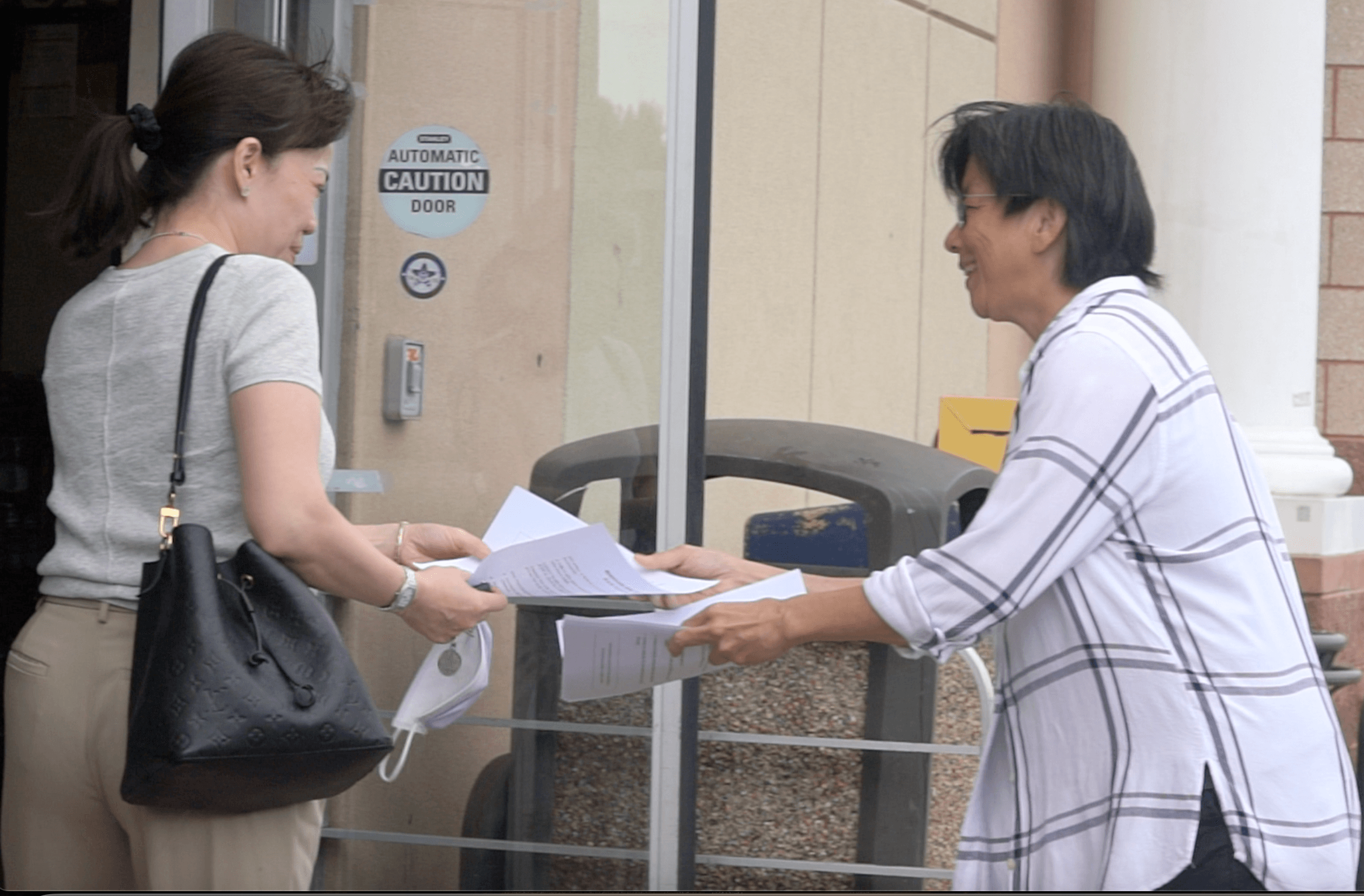

Other Asian Americans who couldn’t canvass in person found alternative ways to support their parties and increase voter turnout.

On WeChat—a social media app widely used among Chinese Americans—Chinese Republican supporters organized donation drives in group chats to fund huge custom Trump-Vance signs, which a representative hung on the pedestrian bridges in high-traffic areas in swing states, positioned directly next to a Harris-Walz sign.

In late August, Yukong Zhao, a Chinese Floridian and education advocate, collaborated with Holly Ham, a Korean American and former U.S. government official, and founded a national alliance called “Asians Making America Great Again(AsiansMAGA)”. They mobilized peer Asian American communities to campaign for Trump in swing states and communicate Trump’s vision to Asian communities through multiple Asian language media advertising and social media.

In a virtual meeting aimed to train participants how to convey messages if interviewed by media about how Asians view the campaign, Zhao repeatedly stressed that even though some Asians might hold strong opinions towards other groups of people of color, they must avoid racial attack to the Democratic presidential nominee and focus on her weak policies instead.

At AsiansMAGA, members promote Republican policy agendas they believe benefit Asian Americans in areas such as crime, education, and the economy. These agendas are translated into various Asian languages and actively disseminated across social media platforms popular in Asian American communities, like WeChat, Kakao, and Zalo.

AsiansMAGA rallied in Fairfax County, Virginia in mid-September. Photo Credit: Yukong Zhao

Meanwhile, Asian Democrats conduct similar outreach in dedicated group chats with their like-minded peers on the same platforms. Some working in liberal arts and higher education create detailed slide presentations and flyers to explain and visualize Biden-Harris policies in their mother tongue, aiming to demonstrate to their ethnic groups why Democrats are the stronger choice.

Asian Americans are also active in phone and text bank teams for both parties. Beyond those organized by local GOP or Democratic groups, some Asian Americans apply their expertise in research and data analysis to create customized phone and text banking lists that specifically target their ethnic communities. They work to mobilize these voters by offering culturally accessible outreach, speaking their native languages, and sharing relatable immigrant stories to inspire higher turnout.

Adam Xu, a real estate broker in Seattle, currently serves as chair of the “Chinese Americans for Harris” phone bank committee. Cold calling is integral to his work, so he has developed an efficient system for phone banking, which he easily adapted for the campaign. “The key,” Xu said, “is securing reliable contact information for voters.”

They requested that the Harris campaign headquarters provide contact information for Chinese Americans in swing states, aiming to engage this voting bloc in their native language to foster a stronger connection. However, the headquarters had not yet developed such tailored lists for this purpose.

The lack of assistance from the campaign headquarters didn’t stop the Chinese Americans. Xu obtained voter contact information from counties with substantial Chinese American populations by submitting requests directly to county offices in swing states. He then refined the list by filtering for surnames common among Chinese Americans, creating a more targeted outreach list.

Hundreds of Chinese Americans volunteered for phone and text banking using the lists Xu compiled. Xu, along with seasoned phone banking volunteers, provided training that included sample scripts and effective strategies, such as the importance of keeping conversations clear and concise. Volunteers were encouraged to wrap up calls in three sentences if they sensed a lack of genuine interest from the person on the other end.

When making calls, they initiated the conversation in English but pronounced the recipients' names with accurate and respectful Chinese intonation. If the recipients exhibited any indication of being Chinese, the volunteers promptly switched to Mandarin, aiming to establish a sense of familiarity and connection. Collectively, they had made tens of thousands of phone calls and sent text messages to all seven swing states.

Phone banking also gained popularity among Vietnamese communities in California. Given that many Vietnamese work in the manicure industry, they have established a robust phone banking network among nail salon workers. Callers reminded community members to register to vote. The Vietnamese community in California affectionately refers to these volunteers as “aunties.”

“Our aunties have essentially been older so, you know, like when the older aunties calling you, the person on the other line may be less likely to hang up or more likely to stay on the phone,” said Lisa Fu, the executive director of the California Healthy Nail Salon Collaborative, as she praised the effectiveness of the nail salon phone banking networks and the influence of “auntie power.”

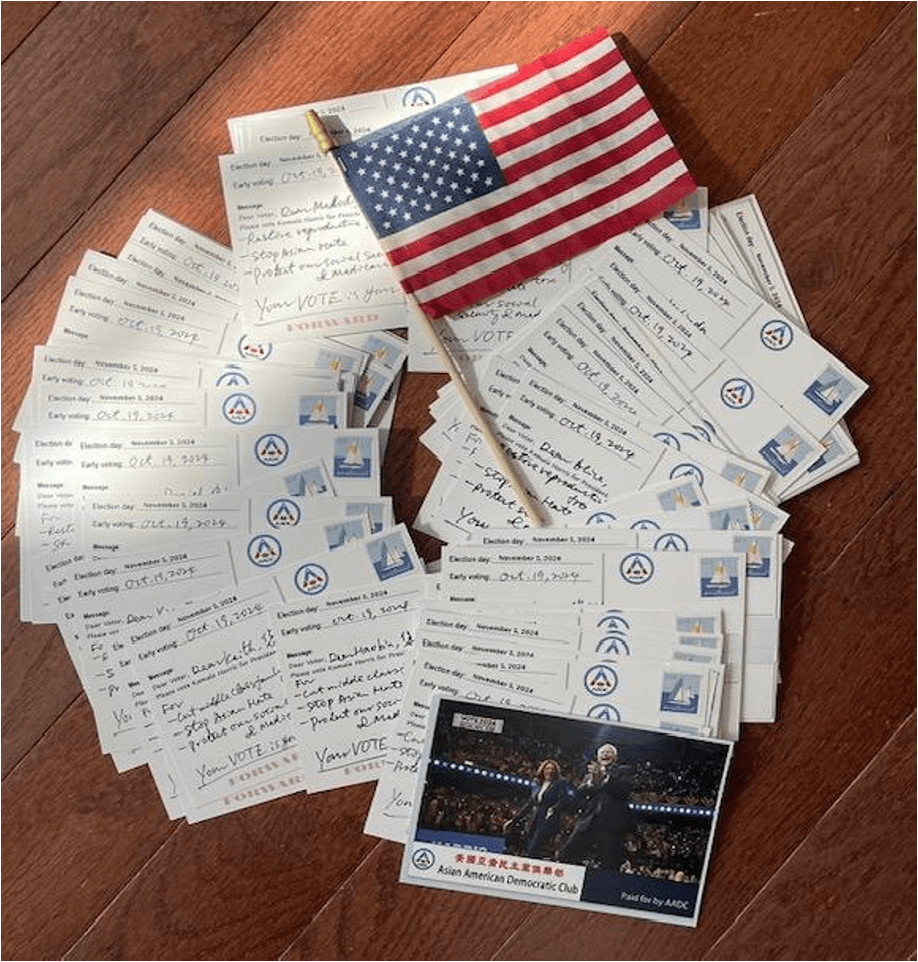

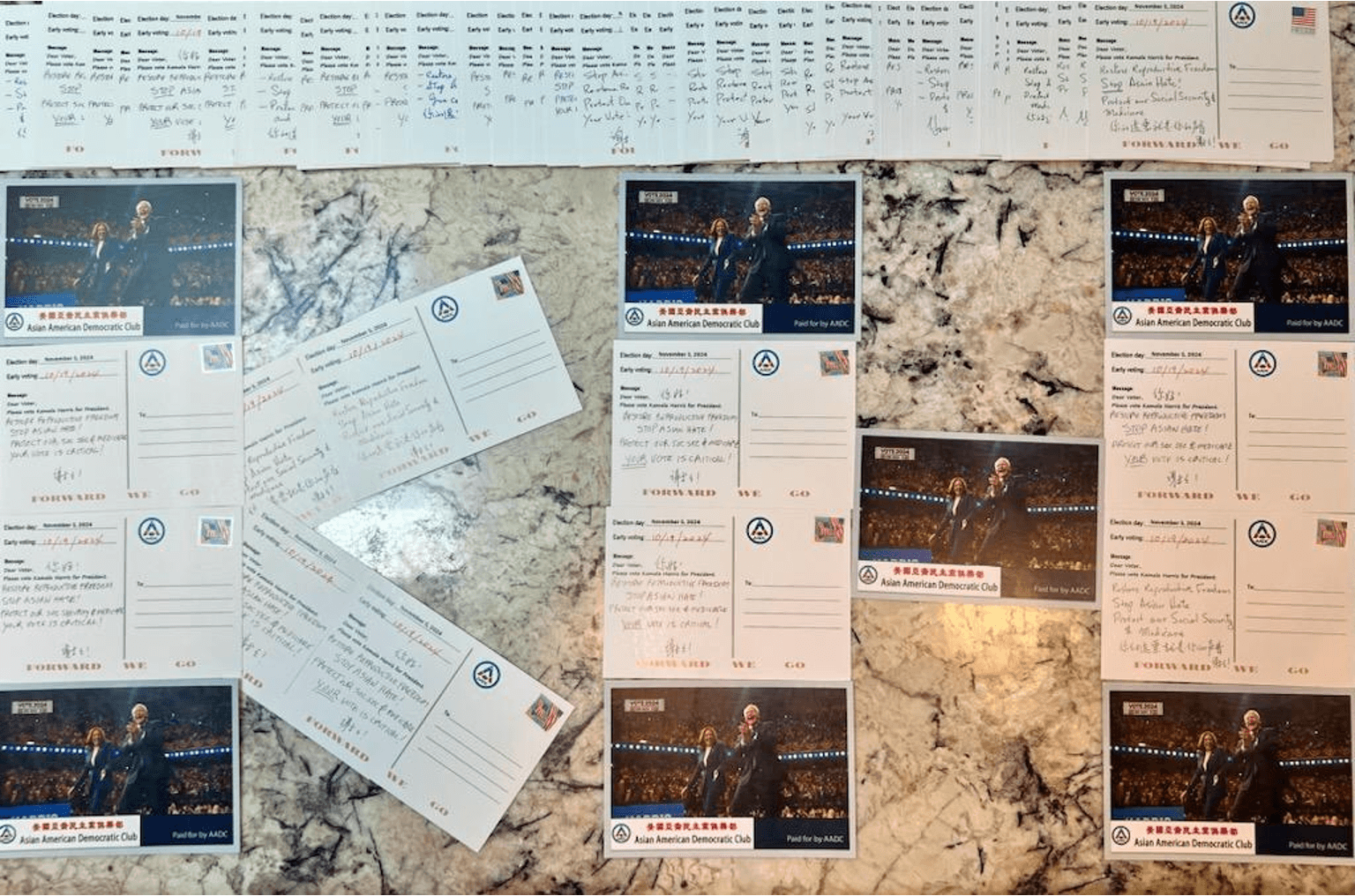

In addition to utilizing social media, phone bank and text bank in multiple languages, Asian Americans also employed the most traditional methods, such as handwriting postcards and mailing them to voters in swing states.

Xu Zhao is the Co-Chair for “Chinese Americans for Harris” and led the the postcard initiative from Miami Florida. She spearheaded fundraising efforts among Chinese Americans to design, print and purchase stamps for over 5,000 postcards. Over 30 volunteers were assigned to handwrite around 200 postcards each. They expressed greetings and gratitude in Mandarin Chinese while highlighting key Democratic agendas in English.

Handwritten postcards by Chinese American volunteers were sent to Chinese American voters in battleground states. Photo Credit: Xu Zhao

Some volunteers had not written in Chinese for years, and the task of composing so many postcards within a short time frame was no easy feat for anyone.

“It’s way more different from printed postcards, which people may discard without a second thought,” said Ling Luo, founder of “Chinese Americans for Harris.” “But they will appreciate the handwritten ones. They recognize that we have made sincere effort and dedication.” Luo mentioned that she still keeps one handwritten postcard from New York from the last election cycle as a cherished reminder of that effort.

Volunteers placed the postcards in the shape of Kamala Harris’s initials. Photo Credit: Xu Zhao

Driven by Fear or Affection for Trump

Many of the most active canvassers on both sides had previously been quiet or independent voters before 2016. Motivated by either a deep concern or strong support for Trump, they decided to take action—either to oppose or champion him—and to help safeguard the democratic process by boosting voter turnout.

Though Zhu now played a pivotal role in the "Chinese Americans for Harris" campaign, he recalled being a quiet voter before 2016, primarily focused on his family and career in the real estate industry. Zhu found success professionally and enjoyed golfing in his leisure time, distancing himself from politics. “I miss the politics before 2015 when ordinary people didn’t feel compelled to get involved,” Zhu said.

Arriving in the U.S. in 1987 and naturalizing several years later, Zhu consistently supported Democratic candidates, trusting the democratic system’s capacity for self-correction. However, Trump’s emergence prompted him to stand up and actively defend democratic principles. Among the issues that concern Zhu most, combating racial discrimination remained paramount. “I cannot agree with the racist undertone of Republicans,” he said.

Alice Yang(right), a Democrat Chinese American was distributing bilingual flyers in support of Harris at an Asian grocery store entrance in Fairfax, Virginia on an October weekend. Photo by: Pingping Yin

Xu wouldn’t have pursued U.S. citizenship if Trump hadn’t run for president. Holding a green card provided sufficient residency and business rights, even simplifying his travel between the U.S. and China. Now, as a U.S. citizen, he must obtain a visa each time he visits family in China.

However, Trump’s anti-immigrant campaign rhetoric in 2016 troubled Xu. Concerned that non-citizens would face tough challenges under a Trump administration, Xu decided to naturalize the same year Trump took office.

Reflecting on Trump’s term, Xu said his concerns were validated. This motivated him to campaign actively against Trump in 2020 through phone banking, a commitment he has upheld this election cycle. Although deeply involved, Xu doesn’t align with all Democratic positions, particularly in foreign policy. For Xu, supporting the Democrats is primarily about opposing Trump.

If the Republican nominee had been someone else this year, Xu admitted he wouldn’t have been as deeply engaged in Harris's campaign, though he’d still vote Democrat. “This time is different. We can’t afford to lose. If Trump wins, it would feel like the sky is falling.”

In contrast to Xu, Renee Feng decided to pursue US citizenship driven by her support for Trump. This year will be her first time being eligible to vote in a general election after over a decade in the U.S.

Living in Rockville, Maryland, a deep blue district in Washington’s suburban area, Feng struggled to find local Trump supporters. Instead, she connected with allies on WeChat and has driven to Eden Center almost every weekend since September to volunteer with other Asian Republicans.

Feng’s eldest daughter turned 18 earlier this year and also will be voting for the first time. However, she doesn’t share her mother’s political views. They debated and agreed not to intervene in each other’s voting choices.

“She calls me racist. She thinks I lack empathy for vulnerable groups,” Feng said. “I admire her compassion and empathy. But she’s young and doesn’t carry the financial burdens I do. She doesn’t pay taxes, so she won’t fully understand,” Feng said. She mentioned the tax burden every time she tried to convince a passerby to support Trump.

Sarah(third from right) and Renee Feng(fourth from right) campaigned for Trump at Eden Center, Falls Church Virginia. Photo by: Pingping Yin

Dokmai Webster, a Thai-American small business owner in the IT sector supporting the federal government, identified as an Independent for most of her life. “I’m not dedicated to one party line. It’s more about policy,” Webster said. However, since 2016, she has aligned herself with the Republican Party and consistently voted for Trump.

Border control is among Webster’s top concerns. She blamed the Democrats for funding undocumented immigrants. “What baffles me is we're putting them up in hotels and giving them cell phones and giving them money. Where our veterans are homeless and needing the care that they should be getting from the veterans, you know, the VA hospitals and they're not getting that,” Webster complained. As an Air Force veteran, she said it was unacceptable.

Although Webster was unbothered by Trump’s rhetoric toward Asian communities, she acknowledged that his personality is not particularly appealing. “There are a lot of things that he says in his speech. I just cringe. It's like, oh my god, Mr. Trump, don't say that! But at the end of the day, if you look at his accomplishments and what he's done when he was in office, it's fantastic!” Webster said.

David Hoang and his wife, both federal contractors in computer programming, have been U.S. citizens for decades. However, Hoang had never voted until 2020. He said that they were driven to be more engaged by Trump’s leadership and disillusionment with the Democrats.

Many policies implemented by the current Democrats reminded them of the communist regime they fled in the 1970s, according to Hoang. His wife shared that she has grown wary of speaking openly about her political views in their Northern Virginia neighborhood, where Democrats are the majority. She even expressed concerns about giving Yuan Media an interview.

After connecting with Sarah and other Republican Asian supporters, they decided to canvass for Trump, drawn by their conviction that Trump could repair a compromised democratic system. “If this country fails, we’ll have nowhere to go,” said Hoang’s wife.

Championing Asian Communities, Not Just Presidential Candidates

Though often featured by Fox News as a prominent Asian American Republican, Yukong Zhao noted that the GOP has historically overlooked Asian voters as a critical voting bloc. In past presidential elections, margins of victory in swing states have been as slim as 2%, while the Asian American population in key swing states like Nevada has reached double digits.

Zhao said Asian Americans represent a significant influence that should not be underestimated. However, according to a recent AAPI Data and APIAVote survey, outreach from both major parties toward Asian American communities remains limited. Only 62% of Asian American voters reported contact from the Democratic Party, while 46% reported outreach from the Republican Party.

Zhao’s advice to politicians aiming to win support among Asian American voters was to “really address the key concerns of Asian voters.” He further explained that Asian Americans are far from monolithic; distinct national origins and cultural backgrounds foster diverse perspectives, and they won’t collectively support any single party. Zhao also raised the crucial role of language accessibility in campaign materials, as 71% of Asian Americans are foreign-born, with only 57% reporting proficiency in English.

Yukong Zhao delivered a speech at an AsiansMAGA rally explaining Asian voters’ concerns in mid-September. Photo Credit: Yukong Zhao

Xu acknowledged that while the efficiency of phone bank, text outreach, and postcard campaigns might not be ideal despite volunteers' enthusiasm, it remains essential to ensure that Asian voters feel neither overlooked nor excluded. He said their turnout strategy is to make this community feel recognized and valued in the electoral process and then go out to vote.

“The political systems in the U.S. and our home countries are worlds apart. For new immigrants, navigating it alone without guidance can be overwhelming,” Xu remarked. Despite his deep involvement, Xu admitted he’s still learning how U.S. politics and policies affect everyday lives in the country he now calls home. “It’s incredibly complex—sometimes, I feel like the blind man with the elephant.”

Luo also underscored the significance of Asian American participation in election campaigns. She founded “Chinese Americans for Harris” not only to support the Democratic presidential candidate but also to demonstrate the collective strength of Asian Americans—an influence that deserves to be recognized and valued, Luo said.

Drawing on her two decades of campaign experience, Luo said that street protests should be regarded as a last resort if one wishes to ensure that the community’s voices are heard because it’s often too late. “Your vote is your voice,” Luo said. “If you’re not seated at the table, you’ll be on the menu.”

“We represent Chinese Americans, but that doesn’t mean we want the next administration to prioritize only our community or the broader AANHPI group,” said Luo. “We hope for an administration that treats every individual in this country equitably. By fostering a just and inclusive society, Chinese Americans, like all communities, benefit from the greater good of justified equality.”

Ling Luo(front row, second from the left) and other “Chinese Americans for Harris” volunteers at a Harris rally in Houston, Texas on October 27. Photo by: Lin Xu

Pingping Yin

Pingping Yin John Gao

John Gao Eileen Wu

Eileen Wu Akshan Ranasinghe

Akshan Ranasinghe Hansen Zhang

Hansen Zhang